Pharmaceutical Roots is a content series from LGC Standards - investigating and outlining the natural origins of pharmaceutical substances, and offering a deeper dive into their history, uses, risks, and mechanisms of action. This month, we look at how varenicline - aka Champix, or Chamtix – appeared to offer a solution to the global ‘tobacco epidemic’ before production was largely halted by the nitrosamine drug substance related impurity (NDSRI) N-nitroso-varenicline.

From Columbus to a ‘tobacco epidemic’

Christopher Columbus unknowingly missed the chance to save millions of lives during his epic first voyage of discovery - when he had second thoughts about a new, and seemingly useless plant.

Sailing into what is now the Bahamas in October 1492, Columbus and his crewmates were presented by friendly natives with some strange, dry leaves that gave off a powerful odour. But, as they were inedible, they threw them overboard. It was only weeks later, in modern-day Cuba, that they observed local people chewing or smoking rolled tabacos herbs, as Native Americans had done for at least two millennia for medicinal and religious purposes.

The addictive properties of the Nicotiana tabacum plant soon made it a hit with Columbus’ sailors, and it was also famously introduced to Queen Elizabeth I’s English court by Sir Francis Drake in the 16th century. Just over 50 years after being underestimated by Columbus, tobacco was being grown commercially in Brazil, while by the 18thcentury American revolutionary commanders used their country's valuable tobacco crops to fund the War of Independence against the British.

Although chewing remained the most common way of consuming tobacco until the late 19th century, automatic production machinery helped make cigarettes the pre-eminent choice soon after. Tobacco use reached new heights during the First World War – when “Millions of cigarettes were distributed free to the troops in France, and they became so powerful a morale factor that Gen. John Pershing demanded priority shipment to the front.”

During the 1920s and 1930s, cigarette companies launched new brands designed to appeal to women – Marlboro cigarettes were originally marketed with the tagline ‘As Mild as May’ – and tripled the number of female smokers by 1935.

Although the deadly health effects of tobacco were not widely known at this point, unpleasant smoking symptoms such as “scorched lungs” had been noted by the Chinese philosopher Fang Yizhi in the early 17th century, while Sir Francis Bacon discussed tobacco’s addictive properties at around the same time. German doctors began warning pipe smokers about the possibility of developing lip cancer in 1795, and sharp increases in lung cancer amongst American men between the 1930s and 1950s gradually led scientists to demonstrate the close links between tobacco and ill health. In 1955, See It Now became the first television programme to report the connection between smoking and cancer – when its famously heavy-smoking host Ed Murrow for once declined to light up during the broadcast.

Today, despite overwhelming evidence that tobacco is responsible for numerous cancers – as well as a host of other conditions including heart and lung disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and arthritis – we remain in what the World Health Organisation (WHO) calls a ‘tobacco epidemic’. Columbus’ apparently worthless leaves make tens of billions of dollars in profits for the global tobacco industry per annum, but at the expense of more than eight million lives every year – the vast majority of them in lower- and middle-income countries. As WHO points out, “All forms of tobacco use are harmful, and there is no safe level of exposure to tobacco.” The availability of drugs or other treatments that can save lives by helping people defeat their tobacco addiction is therefore critical.

Answers for addiction

Perhaps the biggest problem with weaning smokers off nicotine – the natural alkaloid present in all tobacco plants – is that it is a powerful and highly addictive stimulant. Readily absorbed into the bloodstream, nicotine is able to cross the blood-brain-barrier in just seven seconds, and binds to cholinergic receptors in the brain, muscles, heart, adrenal glands and other vital organs. In doing so, nicotine competes with the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which stimulates receptors in order to maintain healthy functions - including breathing, heart function, muscle movement, and memory. However, nicotine disrupts normal brain function, prompting chemical changes and addiction.

Cytisine, first isolated from the Cytisus laburnum shrub in 1865, is an alkaloid whose effects are “qualitatively indistinguishable from that of nicotine” – so much so that German and Russian soldiers smoked it as a substitute for tobacco during World War Two. Still relatively unknown outside central and Eastern Europe, cytisine was developed behind the Iron Curtain as a smoking cessation aid called Tabex, which first came to market in 1964 – long before any comparable drugs were approved in the West. Although Tabex proved superior to nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) in helping people quit smoking, it also causes side-effects ranging from cold and flu-like symptoms to nausea and vomiting, sleep disorders and even hospitalisations. It is therefore not approved for human use by the European Union or the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Encouraged by the partial success of Tabex, Pfizer investigated cytisine analogues as alternative smoking cessation agents, and by 1997 had developed Varenicline. Preclinical trials demonstrated that “varenicline may not only attenuate nicotine reward and intake, but could reduce the risk of relapse and mitigate withdrawal symptoms in nicotine-dependent subjects”, while also suggesting that it had low potential for abuse. Following randomised clinical trials involving more than 3,600 subjects in the US, the FDA approved varenicline as a smoking cessation aid on May 11, 2006. Marketed as Chamtix, or Champix, the drug immediately proved a spectacular success, with five million people taking it around the world by 2008. As of 2023, it has been prescribed to an estimated 24 million people globally, received approval in 116 countries, and is a WHO Essential Medicine.

Mechanism of action

Varenicline has a dual agonist-antagonist mechanism, consisting of two pharmacological activities, on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). It is both a high-affinity partial agonist of the α4β2 nAChR, and was later shown to be a high affinity partial agonist for α6β2-containing (α6β2*) nAChRs, which also play a key role in nicotine dependence. Agonist activity is a result of nAChR desensitisation and activation, as nicotine causes extensive desensitisation of nAChRs. Therefore, replacing nicotine with another nAChR agonist can reduce nicotine craving. Competition of a nAChR agonist with inhaled nicotine results in an antagonistic activity by decreasing nicotine receptor occupancy of α4β2 and α6β2* nAChRs.

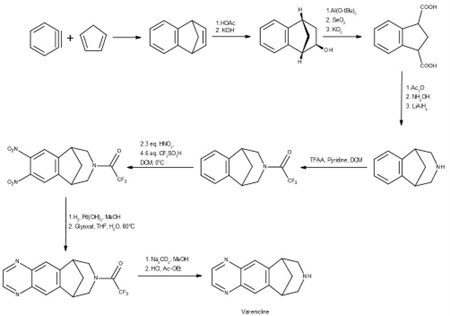

Synthesis

The ’global tragedy’ of N-nitroso-varenicline

In July 2021, Pfizer halted varenicline production because of the presence of the potentially carcinogenic impurity N-nitroso- varenicline, and withdrew all lots of the drug two months later – “effectively making it unavailable indefinitely”. Although generic alternatives were found in Canada, the US and Australia, the recall led to an immediate 75 per cent reduction in varenicline prescribing in the USA, meaning that many patients “simply did not receive treatment”. According to an article in The Lancet in May this year, the move also means that “varenicline is largely unavailable worldwide and fully unavailable in the UK, EU, Japan, South America, and most of North America” – a shortage that the UK NHS warns may continue into the long term. The Lancet also called the recall “a global tragedy for the fight against the tobacco epidemic”, and “a missed opportunity to prevent chronic diseases or death in hundreds of thousands of smokers”. Without a safe and regular supply of varenicline, it said, clinicians had to fall back on less effective regimens, such as NRTs, and “often feel powerless in their efforts to help patients using tobacco”.

LGC Standards – for all your varenicline testing needs

To support your analysis and help ensure the accuracy of your quality control processes, LGC Mikromol supplies an ISO 17034-accredited pharmaceutical API reference standard for varenicline tartrate, and a new impurity standard for N-nitroso-varenicline. Why not browse our fast-growing range of impurity products in the table below? And explore our full range of Mikromol API, impurity and excipient reference standards here.

Also part of LGC Standards, TRC provides a very broad range of research chemicals to support your varenicline and cytisine studies - including key deuterium labelled products, metabolites, and impurities.

|

Varenicline tartrate - MM3380.00 | N-nitroso-varenicline - MM3380.20-0025 |

|

|

Other related products

Part Number | Cas Number | Part Description |

230615-52-8 | 2,3,4,5-Tetrahydro-1,5-methano-1H-3-benzazepine Hydrochloride | |

230615-70-0 | 7,8,9,10-Tetrahydro-8-(trifluoroacetyl)-6,10-methano-6H-pyrazino[2,3-h][3]benzazepine (N-(Trifluoroacetyl)varenicline) | |

230615-69-7 | 2,3,4,5-Tetrahydro-3-(trifluoroacetyl)-1,5-methano-1H-3-benzazepine-7,8-diamine | |

230615-59-5 | 7,8-Dinitro-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-3-(trifluoroacetyl)-1,5-methano-1H-3-benzazepine |