Pharmaceutical Roots is a content series from LGC Mikromol investigating and outlining the natural origins of pharmaceutical substances, and offering a deeper dive into their uses, risks, and mechanisms of action.

Introduction

Worth close to $100 million in sales each year, and a staple ingredient in some of the world’s most trusted medicines for many decades, the expectorant guaifenesin has its roots in the discovery of the New World more than five centuries ago. Its history is already intertwined with one of humanity’s biggest crises, as well as its technological and commercial advances, and yet it still may have more to offer us in terms of developing novel therapeutics.

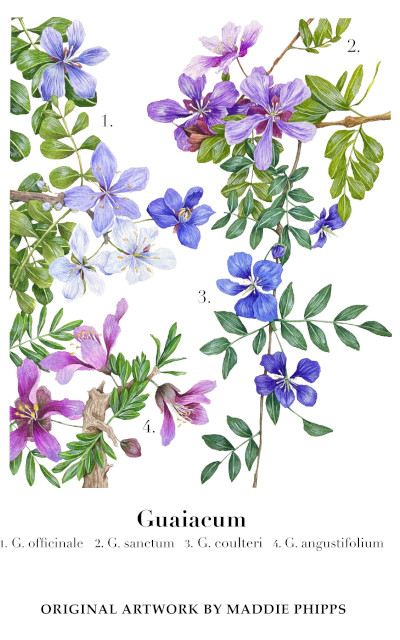

Guaifenesin is derived from plants of the small Guaiacum genus – a family of slow-growing trees and shrubs that grow naturally from the Bahamas to Venezuela. Guaiacum trees are valued both for their beauty – producing plentiful sky-blue flowers in spring, and orange seed pods in autumn – and their ultra-hard and heavy wood. The oily finish and high relative density of guaiacum wood means it is ideal for use in construction and engineering - such as making friction-free bearings for ocean vessels, including the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus.

History

Despite its plentiful engineering applications, it was guaiacum’s medicinal properties that earned it the reverential Latin name - lignum vitae, or ‘Tree of Life’. For centuries, the resin extracted from guaiacum trees has been known for its ability to treat sore throats and rheumatic pains, while it also exhibits general anti-inflammatory, laxative and diaphoretic (sweat inducing) effects. Guaiacum gum was also used as to stimulate menstruation and to induce abortions – most notably in a scandalous 18th-century court case featuring the daughter of the Third US President, Thomas Jefferson. But it was an unfounded reputation - as a cure for syphilis - that first put guaiacum on the global map.

A study of language in the USA claims that ‘guaiacum’ – the name that the Taino people of the Bahamas gave the tree and its resin - was the first word of American origin to be used in English. That achievement is probably due to the fact that, by the early 16th century, guaiacum was believed to be effective against syphilis – an epidemic of which had claimed an estimated 10 million victims by 1510. The word ‘guaiacum’ first appeared in a Latin medical treatise written in 1519 by Ulrich von Hutten, himself a syphilis sufferer, and it was soon popularised as a potential cure by the Italian physician Francisco Delicado. Delicado’s own treatise - On How to Employ the Wood From the West Indies, a Beneficial Remedy for any Ulcer and Incurable Disease – credited guaiacum with curing the syphilis in his 23-year-old son. Although this may have been a case of spontaneous remission, desperate Europeans were becoming increasingly inclined to believe that a cure for syphilis could be found in the place where the disease was thought to originate – the Americas. This frenzied demand greatly increased the commercial value of guaiacum, particularly since its wood and bark were imported into Europe by a monopoly controlled by the giant Fugger mining and banking corporation – described historian Peter Lewis Allen as “the Rockefellers of their day”.

“The syphilitic rich imbibed guaiac(um) cocktails as often as they could,” Allen adds, “and the city of Strasbourg even provided these decoctions free of charge to all of its citizens who were afflicted with the pox.” As another scholar points out, the boom in guaiacum – which was, after all, next to useless as a cure for syphilis – was little more than a “brilliant sales campaign” from one of the world’s earliest and most influential capitalist institutions.

Although highly dangerous, mercury replaced guaiacum as the leading treatment for syphilis during the 17th century, and “lignum vitae gradually sank into obscurity in the pharmacopoeia.” However, it continued to be useful in treating rheumatic conditions until the late 1800s, when it was overshadowed by the development of acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin. Another half-century then passed before guaifenesin was synthesised from guaiacum, and it was first formally approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1952. Since then, as drugbank.com points out, guaifenesin has gone on to have “a storied history… and continues to be one of very few - if not perhaps the only drug that is readily available and used as an expectorant.” In 1989, the FDA approved it as an over-the-counter medication – helping make it a key ingredient in many well-known cough syrups and cold or influenza remedies.

Mechanism of action

Guaifenesin belongs to the anisole class of organic compounds, which are characterised by containing a methoxybenzene compound, or a derivative of methoxybenzene. As an expectorant, it acts by decreasing the adhesiveness and surface tension of sputum and bronchial secretions – thus enhancing their output. It also causes an increased flow of gastric secretions that then promote ciliary action – which helps “change dry, unproductive coughing to coughs that are more productive and less frequent.” As drugbank.com adds: “it is also further proposed that such expectorants may also act as an irritant to gastric vagal receptors, and recruit efferent parasympathetic reflexes that can elicit glandular exocytosis that is comprised of a less viscous mucus mixture.”

Synthesis

Guaifenesin:

Methocarbamol:

Outlook

Despite its efficacy as both a traditional and commercial medicine, guaifenesin has been relatively little-researched in recent decades. However, there are some signs that that this situation could be about to change.

Firstly, guaifenesin was one of many compounds whose repurposing against Covid-19 was suggested at the start of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic – based on its ability to bring about more productive coughing and thus combat Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

The drug is also used as a centrally acting muscle relaxant in combination with sedatives and analgesics in large animal surgery, while another guaiacum glycerol ether, methocarbamol, is used as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant to control discomfort caused by arthritis, osteoporosis, and osteoarthritis. Thus, guaifenesin’s potential effects on CNS system pathways that regulate airway functions were cited by a recent study in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases that argued there was “a clear need for further investigation of GGE (guaifenesin) in patients with SCB (stable chronic bronchitis).”

There has also been interest in guaifenesin’s potential as an anticonvulsant medicine, after Iranian researchers discovered in 2013 that it protected mice dosed with pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) from tonic-clonic convulsions and PTZ-induced death. Speculating that this anticonvulsant activity may be related to guaifenesin’s role as an NDMA antagonist, and noting its strong safety record, they recommended that human clinical trials should be held in future “to address its usefulness in absence seizure in humans”. A Chinese study last year also identified guaifenesin coupled with another naturally derived compound, andrographolide, as a potential therapeutic combination against epilepsy – again, based on their interaction with NMDA receptors.

To support your analysis and help ensure the accuracy of your quality control processes, LGC Mikromol and TRC supply a wide range of API and impurity reference materials for guaifenesin and methocarbamol, certified to ISO 17034 and ISO 17025.

For more in the extensive Mikromol range of quality API, impurity and excipient reference standards for the pharmaceutical industry, explore our full range.

|